view scan

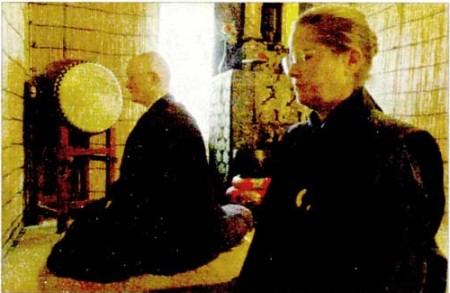

Nyogen and his wife, Ewa Hadydon, practice zazen (Zen meditation) at their house

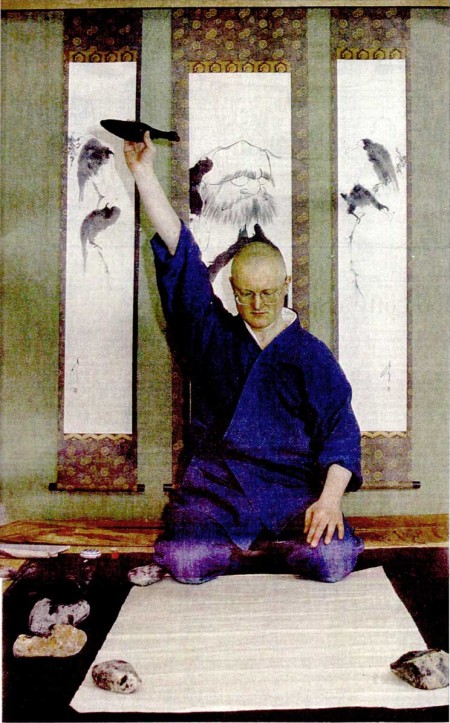

Nyogen Nowak focuses all his attention on th paper before drawing a Zen circle, enso, at his studio in Sendai.

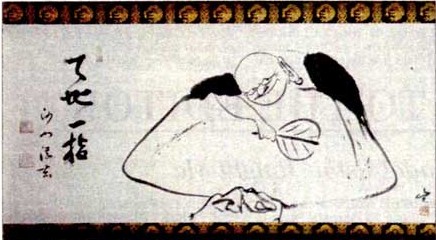

Nowak's painting of "Hotei" (the God of Contentment) featuring calligraphy that reads "Tenchi Ishhi" (All Universe—one finger) by his mentor, Tangen Harada, the roshi of Bukkokuji temple in Fukui Prefecture

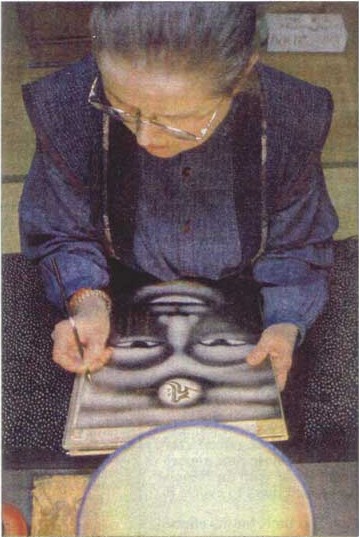

Hadydon writes Sanskrit letters, called bonji, in gold ink.

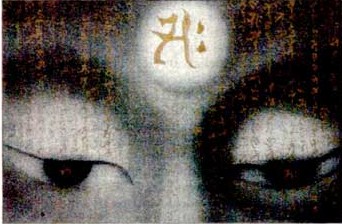

Hadydon's painting of Seishi Bosatsu decorated with bonji

Sendai—Nyogen Nowak raises before drawn and starts every day with Zen meditation and sutra chanting. He has kept up this routine for more then 30 years. But if not for a gift for mother on his 15th birthday, the 48-year-old Pole would never had the life of a Zen monk in Japan

In 1971, his mother was looking for a book to give her only child for his birthday, and a bookstore clerk recommended a copy of "Buddhacarita" (The Life of Buddha)—a Sanskrit poem on the legendary history of Buddha

Nowak was fascinated with the beautiful poem and developed a passion for Buddhism.

"Before reading the book, I had no interest in philosophy or religion. Although I was born in Europe, Christianity didn't appeal to me at all," Nowak said.

When Europe was divided by the Iron Curtain, Poland was under a communist regime dominated by Marxist-Leninist ideology. But the regime did tolerate the Roman Catholic Church, into which more then 90 percent of Polish children are said to have been baptized in the 1970s and '80s.

"Buddhism is a matter of learning something through actual practice rather then having blind faith in the religion. Spiritual awakening occurs only after one practices zazen (Zen meditation). This has enormous appeal to me," Nowak said.

He also spends considerable time in Zen ink painting, or zenga, at his home in Sendai. As part of his routine, Nowak draws enso, a circle painted by ink by Zen monks that represents enlightenment, encompassing the universe in a never-ending line. The simple circle by a single stroke of the brush reveals the artist's state of mind. Nowak said, "Each time you draw enso, it will be different. That's why it's very interesting," he added.

Born in 1956, the native of Wroclaw, Poland, was first interested in oil paintings by surrealists, such as Salvador Dali, and studies surrealism on his own. But he found the aesthetic beauty in the simple black-and-white style of zenga unlike anything he could find in colorful Western paintings.

"I was moved by the great serenity in zenga painting," Nowak recalled. "For me, growing up in Western culture, such serenity was so fresh. Differences between dynamic and static cultures fascinated me."

In addition the enso, Nowak depicts small animals, Bodhidharma and other Buddhist object, incorporating Zen principles of line, color and the use of space into his work. Nowak said the most important element he learned about zenga is bokki—the vital life energy that flows through ink.

"If a line brims with the energy, the whole painting is alive still today even if it was done 300 years ago. This energy can by cultivated by practicing zazen," he said.

Nowak's 53-year-old wife, Ewa Hadydon, also devotes herself to Zen practice and Buddhist art. She has been given daishi, a title for a lay woman who has received Zen Buddhist precepts.

Her work includes the "Mandala of 13 Buddhas," whose face are depicted in precise detail and adorned the drawings with Sanskrit letters, called bonji. Buddhist art, which she said is a visual form of Buddhist teaching, has continued to fascinate her and has inspired her to depict images if Buddhas using a combination of Western and Eastern painting techniques.

Their paintings have been put on public display at various exhibitions in Japan and Poland, and have been received well.

"Their paintings well reflect the spirit of Japanese culture and draw viewers into them," said Tetsure Imaizumi of the Fuganokuni Gallery in Yamagata, where the Polish couple holds an exhibition every year.

"I admire their attitude of trying to integrate themselves into the local community," Imaizumi said.

Their 12th exhibition at the gallery is scheduled for June 21-27.

Despite such praise, the couple regards painting as just a part of their Zen practice.

"I'm often asked at exhibitions if I'm a painter of Zen monk. And I immediately reply that I am a Zen monk. Zenga is a byproduct of my Zen practice," Nowak said.

Hadydon shared a similar view, saying "Painting is my practice."

The two believe that zenga embodies the experience of Zen.

Throughout an interview with The Daily Yomiuri, Nowak frequently used the term "en," referring to a Buddhist concept that all things are destined to exist or happen through the harmonious interaction of cause and conditions. He therefore believes his encounter with the book as a boy was not coincidence, but a turn of fate.

Perhaps fate also made Nowak meet Hadydon at zazen meeting in their hometown, Wroclaw, in 1981.

After being introduced to Buddhism, Nowak looked for a Zen monk in Poland to study under, but could not find any, he said. He then met a painter famous for his oriental philosophy-based works who allowed him to borrow books about Buddhism. His Zen meditation started at the painter's studio on 1974.

Six years later, Nowak went to study at the American Zen Center in New York and them moved to Los Angeles, where he met a Korean monk who taught him ink painting.

In 1983, Nowak finally came to Japan—the country he long wanted to visit—to study Zen in earnest, and received training under Tangen Harada, the roshi (Zen master) of Bukkokuji temple in Obama, Fukui Prefecture.

Nowak and his wife visit the temple five times a year to participate in weeklong retreats called sesshin, in which they meditate for most of the day.

Hadydon first started a carrier as a professional graphic designer and painter after studying art at university. Although the artist already began zazen in Poland, her work initially had no connection with Buddhism. But she has drawn into Buddhist art and Zen spiritualism after coming to Japan.

The two married in 1986 in Japan in a Buddhist-style wedding ceremony. Three years later, they settled down in Sendai. Situated in a narrow alley, their traditional-style house is infused with the smell of incense and, with a meditation room, art studio and small rock garden, is well arranged for Zen practice.

They now seem to live in a perfect environment for practicing Zen, but achieving a sense of enlightenment and self-control that lead to selflessness—the main goal of Zen—is not an easy task.

"I still fell immature," Nowak said even after many years of experience. "This is like a journey without a destination."

See also: The Buddhist Channel article